The Shadow of the Future

This is a piece I wrote for internal consumption at work - I’ve edited out most of the stuff that’s GitHub inside baseball, and think it’s still interesting / useful to the general software-developing public.

Over the holidays, I left my laptop at home and hit the beach with a paperback copy of Robert Axelrod’s influential poli sci book The Evolution of Cooperation, a pen, and a notepad. This book takes the results of a computer tournament of the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma and runs with it until it reaches some very interesting propositions about how stable cooperation can be achieved in a population of egoists.

If you’re a Radiolab fan, this premise may sound familiar, and if you’re not, you might be entertained by the episode at inspired me to dig into this book: The Good Show. The third section is about Axelrod’s work, but the whole episode is entertaining.

##Tit for Tat and the Prisoner’s Dilemma

###The Dilemma

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is simple. Two accomplices are being interrogated for the same crime. If they both keep their mouths shut (mutual cooperation), the cops can only stick them for a lesser charge, and they get short sentences. If one rats and one keeps his mouth shut, the one who rats goes free and the one who kept the faith gets sent up the river for a long time. If they both rat (mutual defection), they get more prison than if they’d kept quiet, but not as bad as if they’d kept quiet and been betrayed.

If you like numbers in tables, you could flip the idea around from “years in prison” to “points awarded” and say:

| P2 Cooperates | P2 Defects | |

| P1 Cooperates | P1: 3 pts - P2: 3 pts | P1: 0 pts - P2: 5 pts |

| P1 Defects | P1: 5 pts - P2: 0 pts | P1: 1 pt - P2: 1 pt |

This becomes more interesting when the game is played over and over again with the same players, and they know how the other person has acted in the past. This is the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, and has been used to model all sorts of stuff from mutually assured destruction to the rate that bacterial infections spread.

###Tit For Tat

Robert Axelrod, the author of the book, was interested in studying different strategies for the IPD. He decided to hold a tournament in which strategies submitted by academics would compete against each other and be ranked by average score. The winner was a strategy called TIT FOR TAT (T4T) that started out nice, and then simply repeated the last thing its counterpart did. You cooperate, T4T cooperates on the next move. You defect, it defects.

Axelrod ran the tournament again, and this time sent the results of the first one to the entrants before they submitted their strategies. Again, the winner was T4T, even though the new competitors had all the opportunity in the world to build a stratgy designed to beat the previous champ. This led Axelrod to propose some ideas about how being reciprocal in the IPD, and by extension the real-world interactions that it can model, is a stable and mutually beneficial strategy.

Naturally, reading about stable, long-term cooperation and a simple and widely applicable model of cooperation got me thinking about how it might apply to working together on software. Whether we figure out just how our type of collaboration can be modeled with the IPD, or just look for lessons in Axelrod’s conclusions, I think there’s something useful to be found in Axelrod’s text.

##What makes a stable and mutually beneficial strategy?

What accounts for TIT FOR TAT’s robust success is its combination of being nice, retaliatory, forgiving and clear. Its niceness prevents it from getting into unnecessary trouble. Its retaliation discourages the other side from persisting whenever defection is tried. Its forgiveness helps restore mutual cooperation. And its clarity makes it intelligible to the other player, thereby eliciting long-term cooperation.

###Avoid unnecessary conflict

In Axelrod’s tournament, strategies with ‘niceness’ were overwhelmingly dominant. This meant “always cooperate unless provoked”. Nice strategies were never the first to defect, and did not punish defection with long strings of retaliation in return.

At GitHub, we don’t flee from vigorous debate, so the maxim “avoid unnecessary conflict” seems like it might not work for us, but in this case it might mean “don’t overdo getting your way at the expense of alienating others”. In other words, we need to be clear on what is “unnecessary” and what is “conflict”. This phrasing could also raise a red flag of a different sort, because we want the best code and best work to win - I don’t think that presents a problem for applying the lessons of the book though, because a model doesn’t have to be perfect to be useful.

###Retaliate when provoked

In the later Prisoner’s Dilemma tournaments, overly nice strategies were exploited by clever strategies that played nice for a while and tried to figure out just how much meanness it could get away with. In other words, if strategies were too forgiving, they would not survive.

As I read the book, I found myself struggling with the concept of ‘retaliation’ in the context of software collaboration. We don’t want collaborators to be vindictive or overly political. Perhaps it could be translated as knowing when to say “no” and when to say “justify this to me” – I think this aspect of would benefit from more exploration.

###No grudges

Strategies that retaliated for more than one round did poorly in the PD tournaments. While remaining provocable lets you avoid being exploited, reacting too drastically hurts long-term cooperation. If your counterpart can expect you to cooperate most of the time, he or she will be more likely to come to the table ready to cooperate. This doesn’t work if your partner is spiteful or misinformed as to your strategy, which leads to the next heuristic:

###Be transparent

After Axelrod’s first tournament, he held a second. Everyone that entered received the results of the first tournament, showing TIT FOR TAT’s dominance in long term games. The result was that even tricksy strategies were built to anticipate TIT FOR TAT’s presence and cooperate with it. In this way, the clarity of TIT FOR TAT helped it with stable long-term cooperation.

This clarity will make other participants less likely to try to suss out a (nonexistent) hidden agenda and exploit it, and will help prevent unnecessary conflict and echo effects.

##What kind of environment promotes reciprocity?

Axelrod also talks about how the strategic setting itself can make reciprocity more stable.

[If the interaction only happens once], cooperation is very difficult. That is why an important way to promote cooperation is to arrange that the same two individuals will meet each other again, be able to recognize each other from the past, and to recall how the other has behaved until now.

If we can keep the interaction going, which is what makes the Iterated Prisoners Dilemma iterated, we can encourage mutual cooperation by changing the payoffs of the four outcomes in the game, teaching players values and facts that will promote cooperation, and most importantly by enlarging the shadow of the future.

###The Shadow of the Future

One of the most interesting findings of the book that is returned to repeatedly is that reciprocal strategies are only stable if the value of future interaction is high compared to the current interaction. That is to say, the less important tomorrow is to you, the more likely you are to defect against your counterpart. In the chapter on promoting cooperation, Axelrod gives a few suggestions on how to “enlarge the shadow of the future” and otherwise promote cooperation in general.

One way to make the future more important is to make interactions more durable - make it more likely that you will interact with the same participants again. Making this happen and finding a way to communicate it to the players is an obvious way to make the future more important. Increasing the frequency of interactions has a similar effect.

Unfortunately the easiest ways to concentrate interactions between specific individuals are hierarchies and bureacracies. Those aren’t effective ways to make happy humans, so we’ll have to be more creative. Getting people grouped together by interest accurately and using them to support communication might be a step in that direction.

Another way to increase frequency is to take one big issue/interaction and break it into small pieces. There might be something conceptual there related to the new task lists in pull requests.

And on and on. Beyond trying to apply the specific examples given in the book to our work, “enlarging the shadow of the future” provides an interesting jumping-off point for thinking about how to promote collaboration with our tools.

##Practical Application

Promoting good outcomes is not just a matter of lecturing the players about the fact that there is more to be gained from mutual cooperation than mutual defection. It is also a matter of shaping the characteristics of the interaction so that over the long run there can be a stable evolution of cooperation.

One interesting challenge is that the priniciples supporting cooperation can be read to encourage bureaucracy and specialization. One of our goals is to create an environment that provides durable, frequent interactions through tools and not through a hierarchy, and with software and text, not full-time managers.

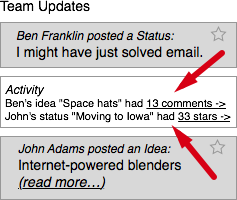

Here are a couple examples of ways to apply these concepts to an internal status app, like the one we use at GitHub. They aren’t intented to be huge, brilliant solutions, but as examples of where this kind of thinking will take you.

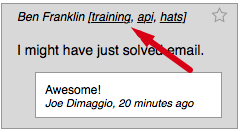

###Transparent strategies in our internal status app

Transparent strategies discourage cleverness and playing to suspected hidden motives. Perhaps we could surface “comment” and “like” activity better in the status feed to make people more aware of how and where others are collaborating.

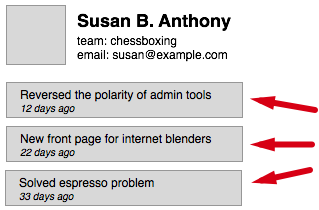

###Ship history

Along the same lines, individuals need to be recognizable for strategies to be transparent. Along these lines, perhaps we could add a ‘recent ships’ along with the ‘recent updates’ on a collaborator’s profile page. This would be a simple list that any user could add to, listing things that the person had shipped - like a trophy wall of things he or she is proud of.

###Team/focus tags

Territoriality can stand in for recognition of individuals - Axelrod has some interesting things to say about this when he explores the evolution of cooperation in animals that can’t tell invidiual entities apart. As our employee count grows, knowing what team someone is on or where their interests lie adds interesting context to interactions.

###Neighboring territories

For cooperative strategies in a territorialized population to invade / grow / colonize, they need to have neighboring territories. Can we use the data we have on a collaborator’s team / topics of interest to find isolated populations and give them neighbors / bridge them to the rest of the company?

##Conclusion

In a situation modeled by the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, reciprocity is the most stable long-term strategy given the right set of payoffs. There are decisions we can make and environments we can support that make reciprocity more likely to succeed and become the dominant strategy in a group. Whether all of our interactions can be modeled thus or not, the ideas of reciprocity, the importance of the future, and the robustness of transparent strategies are all relevant to the work we do on software collaboration, and I hope they can provide an interesting base for discussion.

###Addendum

One way I came up with applying the model works as follows:

- Points are represented by getting changes you advocate into master

- Collaboration is accepting changes from others

- Defection is rejecting changes from others